Although you can’t walk more than a few steps in Philadelphia without running into a reminder of Ben Franklin’s legacy (Franklin’s Philadelphia), the actual homes he lived in are long gone. His only surviving residence is a 1728 brick row home at 36 Craven Street in London. Here he lived for 16 years as an agent for the colony of Pennsylvania and later New Jersey, Georgia and Massachusetts. He returned home for only 18 months during that time. Morphing from a private home to a Victorian hotel, it eventually turned into a squat before being rescued in the 1970’s with most of its original, Franklin era features intact – including panelling, window shutters and staircases.

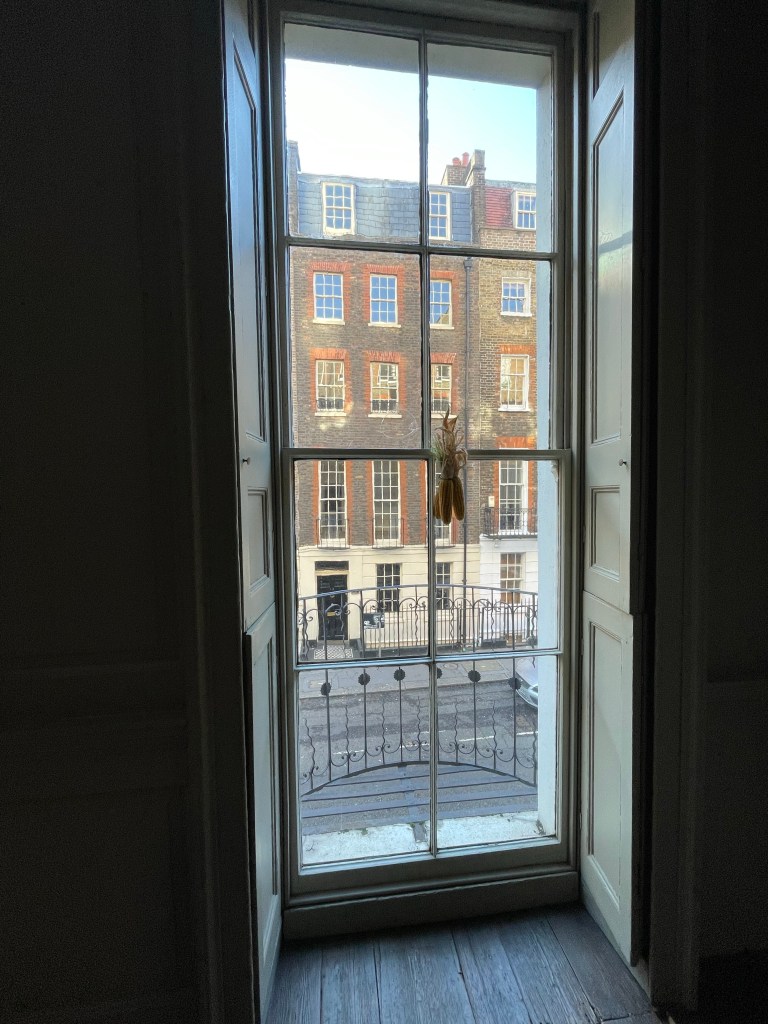

During his lengthy stay in London (during which his wife repeatedly begged for his return, had several strokes, and eventually died) you might have seen Ben Franklin hanging out naked in this London window. It was here that Franklin, a believer in the importance of fresh air, sat most mornings “without any clothes whatever, half an hour or an hour, according to the season.”

While in London, Franklin not only worked in politics, but used the back of his first floor room to continue the scientific experiments that had made him world famous, including refining his Franklin Stove. Today, the fireplaces are still intact, including this one where Franklin’s stove once sat (although only one original mantle remains in a first floor room).

Parts of his actual stove are still on the property, currently hidden away in the property’s cellar, which extends 1/2 way under the street out front, and whose door you can see looking out of the basement kitchen windows.

In 1998 conservationists found more than 1,200 pieces of human bone in a basement pit that was once part of the London home’s garden. Evidence shows that the bones are remains from an anatomy school run from the house by William Hewson, son-in-law of Franklin’s landlady, during the time Franklin was in residence. Many of the bones show dissection marks from surgical instruments. Because procuring bodies for dissection at that time was illegal, it’s likely that some of Hewson’s cadavers came from London’s infamous bodysnatchers.

In 1775 Franklin eventually returned to Philadelphia after the death of his wife required his attendance to manage his affairs (plus, his role as a supporter of the American colonies made his continuing presence dangerous). Deborah had been running his businesses during his absence, once arming herself and running off a mob of protesters angry at Franklin’s politics. Franklin may have been a brilliant statesman, but he was not such a great husband (Ben Franklin’s Ghost House).

In 1860 Charing Cross Railroad Station was built behind Craven Street and the home became a hotel. One remnant from that era, a Victorian stove, can still be seen hidden away in the ladies’ toilet!

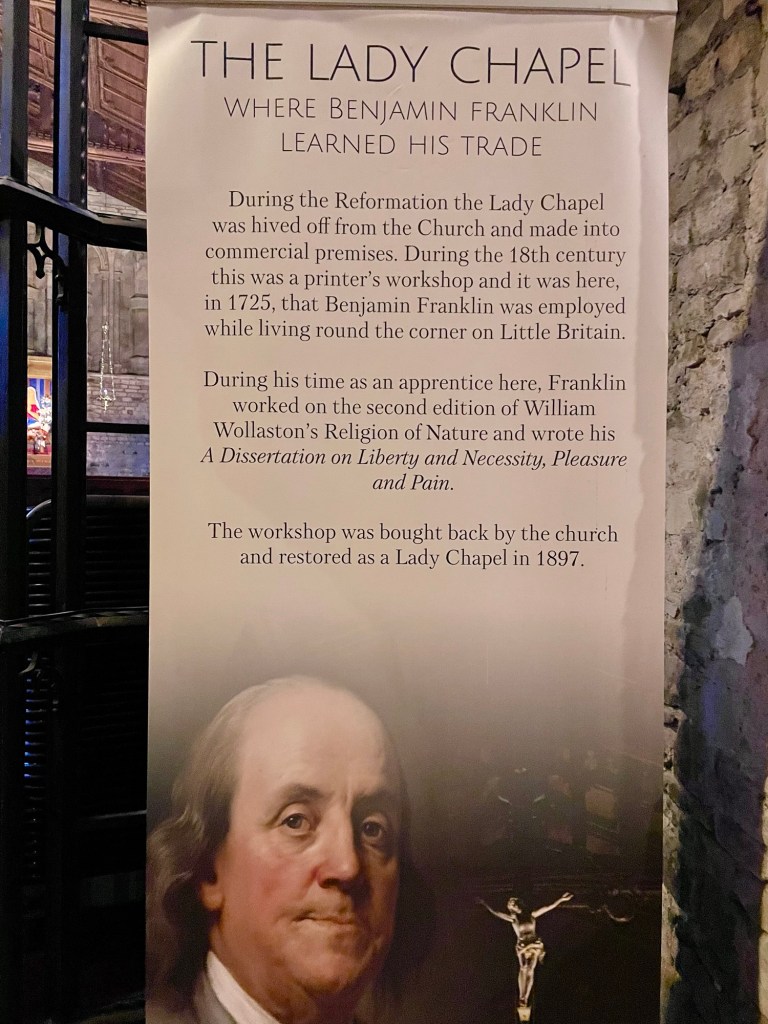

Ben Franklin first visited London in 1724 to gain experience as a printer and purchase supplies under the sponsorship of Pennsylvania’s governor. Unfortunately, the sponsorship never came through so he was stuck in London with no money or job. He took lodgings on Little Britain Street and got a job in a printshop in Bartholomew Close. The building had once been a part of the priory of St Bartholomew the Great. After the dissolution of the monasteries, it became a secular building where several commercial businesses were located in Franklin’s time. It has since been reunited with the church, and is now the Lady Chapel, which you can visit.

During his 18 months in London, Franklin spent “a good deal of my earnings in going to plays and other places of amusement.” He tried to meet Isaac Newton “of which I was extremely desirous; but this never happened.” He also spent time swimming in the Thames, even teaching friends to swim. He eventually worked his way back to Philadelphia, where he became the influential citizen we know today.