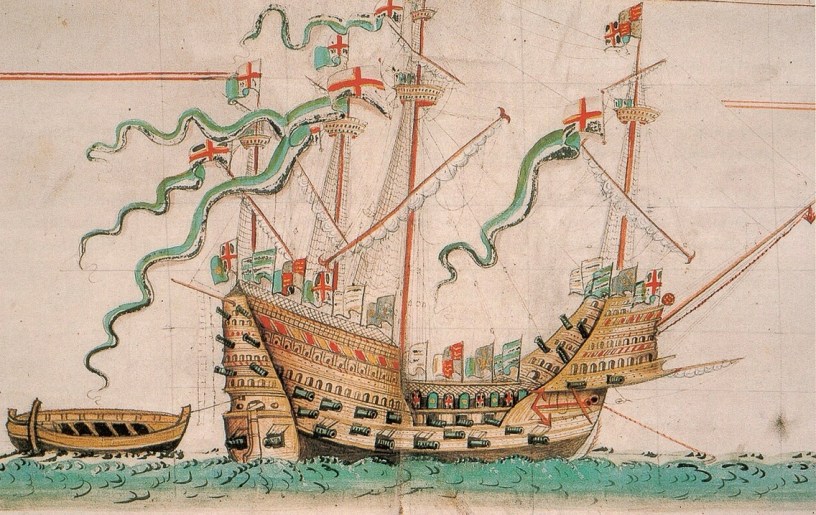

In 1545 Henry the 8th watched from shore as his naval flagship, the Mary Rose, keeled over after her opening volley against the French navy and immediately sank, killing all but 30 of the 415 member crew.

Despite attempts to salvage the ship, it was quickly covered with sediment, protecting much of the ship and its contents for almost 500 years. In 1982 she was finally raised and returned to the Portsmouth dockyard where she had been built in 1510, and where today you can visit the ship and the 19,000+ objects recovered with her.

What is most amazing is the glimpse these objects give into the lives of ordinary Tudors. Whereas most historical artifacts tend to be rare and precious, the kind of treasures passed down from generation to generation, artifacts recovered from the Mary Rose tell the stories of everyday working class soldiers and sailors. Because the ship sank and was buried so quickly, many of the artifacts were still in their original location on the ship, so the contents of cabin’s for the surgeon, carpenters, and cook provide details about their everyday lives, such as the chest found in the master carpenter’s cabin that include this amazing manicure kit:

In fact, one of the biggest surprises was the attention to personal hygiene. The most common personal item found among the artifacts were lice combs – over 82 were recovered.

Contents of storage cabins provide additional everyday details such as diets, types of rigging and weapons.

The kitchen area provided information not only about cooking methods (there were two large brick ovens, each with a huge brass cauldron on the top where meat and fish were boiled), but also diets. Artifacts included barrels full of beef and salted Canadian cod, pig bones, plum/prune stones, grape pips and cherry stones.

Another favorite display was of the archery weapons. Medieval English archers were famed for their skill with the longbow, and although gunpowder weapons were eclipsing these at the time of the Mary Rose’s sinking, 172 yew longbows and over 2,000 intact arrows were recovered, making this the only example of a precisely dated archery collection in the world.

The guns themselves were also impressive. A 1546 inventory lists 39 large guns on board, including this one with the beautiful lion’s heads and Tudor rose on top.

Of the 98 skeletons partially reconstructed skeletons and miscellaneous bones, the most complete was Hatch, a brown, year-old terrier found outside the carpenters cabin.

Archaeologists were able to use location found on the ship and physical injuries to help identify likely careers of several of the other skeletons. Their stories are in displays throughout the museum, which is designed to give a real sense of the ship before it sunk. The display halls run parallel the ship, with each display lining up with its location on the actual ship (visible on the opposite side). Digital displays light up the ship periodically, showing images of the crew at work. The perpendicular hallways display additional artifacts, and provide more detail about the ship and its crew.

To get to the building that houses the Mary Rose, you’ll pass through historic Portsmouth shipyard, whose docks date back to Richard the Lionheart in 1194. Used throughout the Medieval period for wars with France, the port is still one of Britain’s largest naval bases. The first recorded dry dock in the world was built here in 1495, and several of the historic buildings date to the 1700’s. By 1800, the Dockyard was the largest industrial complex in the world, and it was from here that Horatio Nelson set out on the Victory for the Battle of Trafalgar. Today, the Victory is dry docked and can be toured along with other naval vessels (although to see the bullet that killed Nelson, you’ll have to visit Windsor Castle).

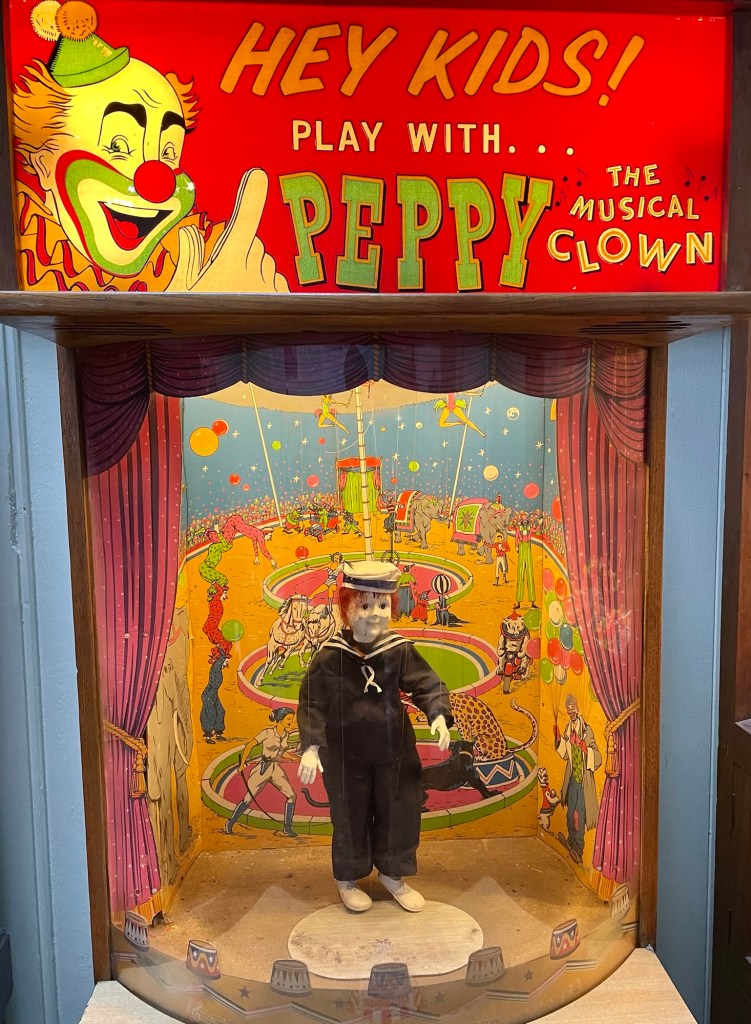

For some non-naval fun, be sure to check out the penny arcade, filled with over a dozen of these early 20th century novelties. Best fun you can have for 20p!