Modern museums grew out of these Renaissance collections of weird and wonderful objects. Also called Kunstkammer (art chamber) or Wunderkammer (room of wonder), they displayed the marvels of the Age of Exploration – exotic natural specimens, man-made works of art, ethnographic items, and scientific instruments. All of these can be found in this 1660 painting by Jan Brueghel the Younger: shells, monkeys, paintings, jewelry, silver, telescopes, magnifying glasses, astrolabes and globes.

When Cabinets of Curiosities emerged in the sixteenth century, they were entire rooms rather than just a single piece of furniture, and a form of Netherlandish genre painting developed to commemorate both the collections and their owners.

Because of their precise details, these paintings are helpful in dating specific paintings and learning more about the individual species represented. The Bruegel painting above contains works by Ruebens, Titian, and the artist’s father, Jan Bruegel the Elder.

Since collecting was a rich man’s hobby, the actual cabinets built to display the items were themselves very beautiful:

Sometimes the rooms were simply wall to wall paintings, which later developed into the salon-style of decorating, with objects hung close together from floor to ceiling.

The rooms were popular with artists who used the objects in their paintings or for inspiration. The Rembrandt Museum’s Kunstcaemer (Dutch) displays a recreation of the artist’s long gone collection:

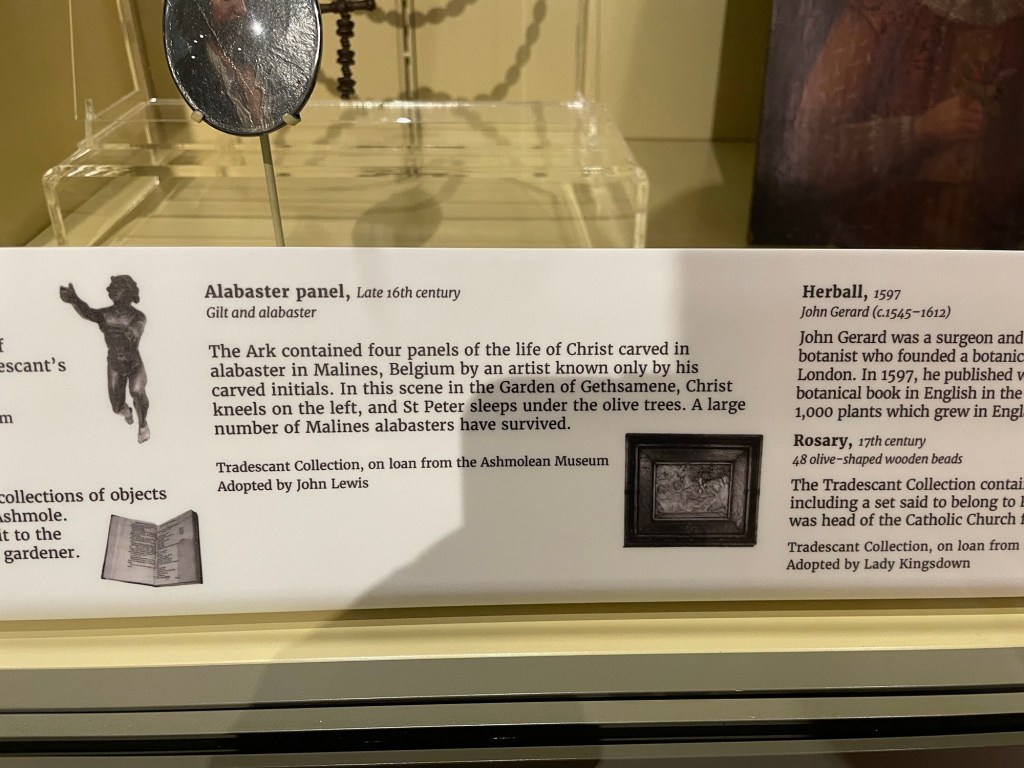

What started as symbols of wealth and sophistication morphed into public museums where anyone could pay to see the exotic collections. The first to open in England was in the London home of the father/son duo of plant collectors, John Tradescant the Elder and Younger. Starting in the 1630’s, “Tradescant’s Ark” displayed their eclectic collection until their deaths, when it passed to their friend Elias Ashmole. He eventually donated it to the University of Oxford, and today items from the original collection can be found at the Ashmoleon Museum and in the Garden Museum, London.

The duo’s amazing tomb (London: Gardeners to Royalty & Their Spectacular Tomb) illustrates part of their collection, including an alligator and shells:

With the dawn of the Enlightenment, the focus on reason changed these artistic jumbles to more ordered scientific collections. In 1784 the early American artist Charles Willson Peale opened his museum in Philadelphia, displaying his collection of portraits of important Americans. Within 2 years he’d added natural history displays, as well as a physiognotrace machine used to draw souvenir portraits.

Although Peale’s Museum is long gone and the mastadon skeleton now lives in Germany, the museum has been partly recreated in Independence Park, complete with part of Peale’s original portrait collection and a few original exhibits, such as this taxidermy eagle, originally a Peale family pet (Secrets of Independence Park: Putting Faces to the Revolution – The Portrait Gallery).

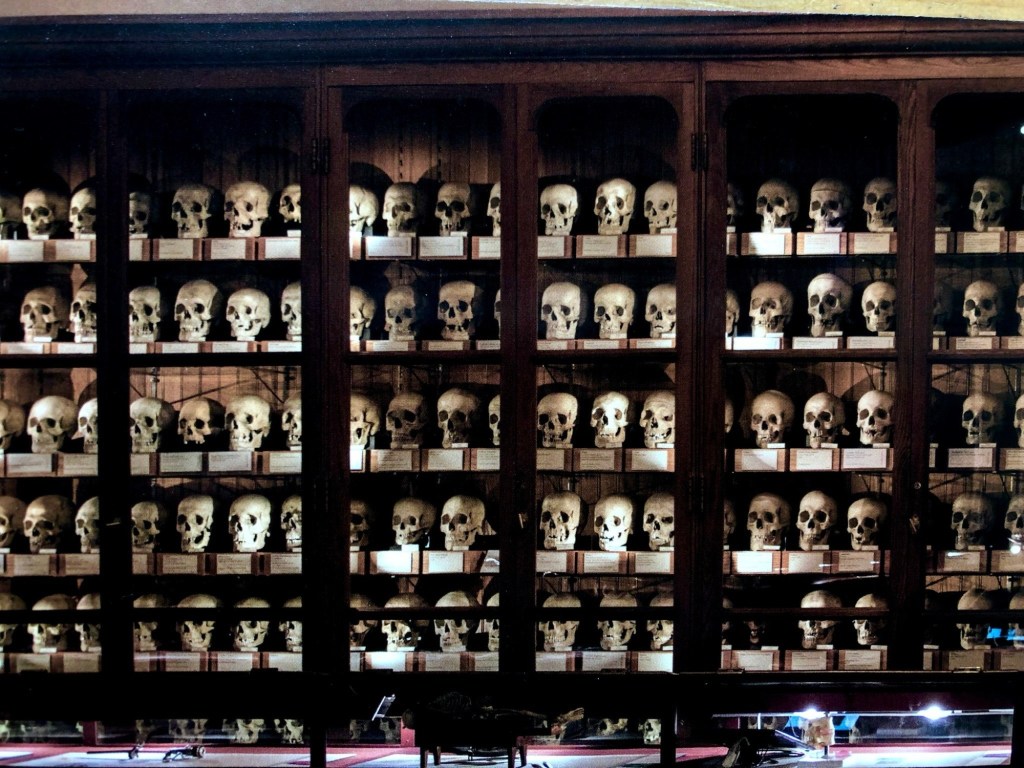

Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum is an excellent example of a Victorian-era cabinet of medical curiosities. No pictures allowed, so this is a postcard of their 19th century Hyrtl Skull Collection. Lots more objects, including drawer after drawer of swallowed foreign bodies removed by their collector, Dr. Chevalier Jackson (Philly’s Creepiest Museum – The Mutter Museum).

Throughout the Victorian era, museums walked a fine line between their original function as displays of curious objects and collections of objects to be studied scientifically. The 1857 geology museum at Rutgers University highlights this dichotomy. It’s a university-sponsored collection, but in addition to the rocks and fossils expected in a geology museum, there is an Egyptian mummy, a giant spider crab that arrived at the university in the late-1800s along with seversal Japanese students, and a stuffed platypus.

The Mercer Museum outside of Philadelphia is an early 20th century take, a labyrinth of a museum exhibiting over 40,000 pre-industrial American tools and artifacts collected in an effort to document a way of life that was rapidly being lost to industrialization (Philadelphia + Architecture = Arts & Crafts (Henry Mercer’s Tiles, Castle and Museum)).

In 1922 Albert Barnes broke from the expected modern style of museum organization, instead choosing to hang his art collection in a way reminiscent of the early cabinets, with paintings hung salon-style interspersed with furniture and ethnographic items as a way to facilitate dialogue between pieces (What’s So Special About The Barnes?).

Today, even among traditional museums, organizing objects in ways reminiscent of cabinets of curiosity is back in fashion.

The brand new Princeton Art Museum arranged this collection of miniatures so that “Objects of differing functions, countries of origin, media, and periods of production sit alongside each other to delight the eye,” a sentiment harkening back to the original cabinets of the 1600s.

Some collections make no pretense of any sort of educational mission, instead using interest and aesthetics to guide their collections, just as they did in the original displays of the 1600’s. The Abita Mystery House in Louisiana stuffs everything from paint-by-numbers to home-made taxidermy onto one gloriously bizarre jumble (Mississippi: Shrimp & Gators).