If you’ve ever wondered about the history of the cultivated blueberry (maybe while eating a blueberry sundae from Hammonton’s Royal Crown??), its origins can be traced back to this company town in the Pine Barrens of New Jersey and to Elizabeth White.

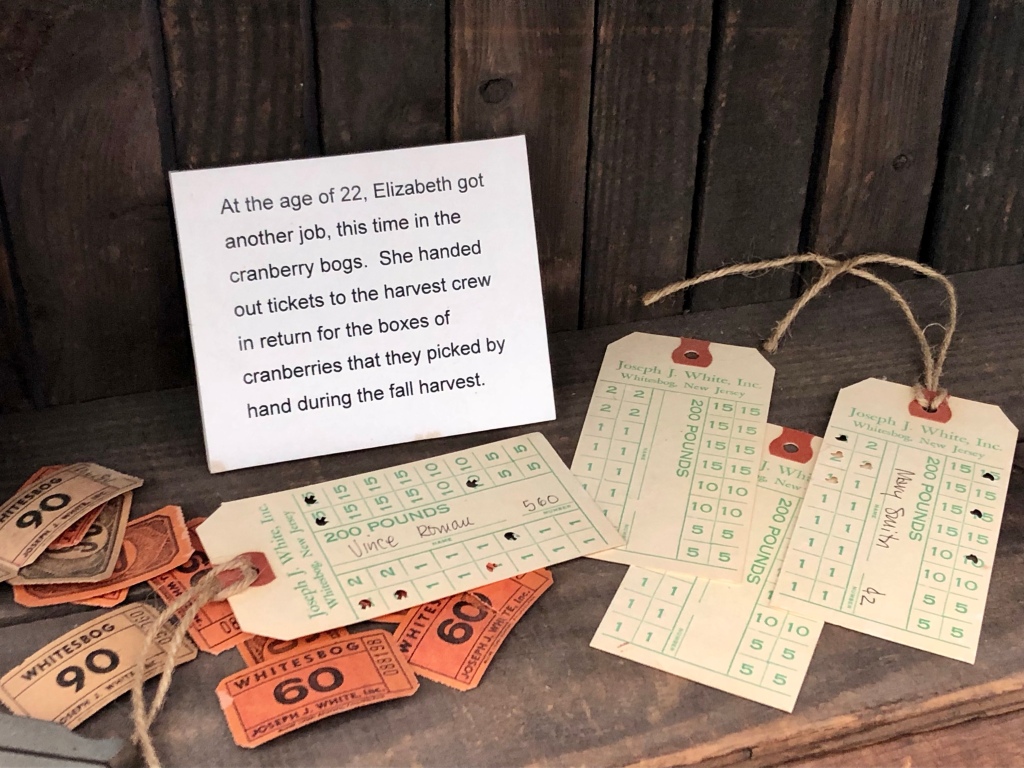

Elizabeth was New Jersey cranberry royalty. Her grandfather started the bogs at Whitesbog, and her father, JJ White, added to it when he married into the family, thus creating one of the largest cranberry farms in the country. Elizabeth loved the business, and helped out at an early age – from handing out tickets to the pickers, to working with a New Jersey State entomologist to reduce the effects of the veracious cranberry katydid.

Her adventures in blueberry propagation began in 1910, when she saw a notice in a USDA publication written by Frederick V. Coville, a chief botanist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which discussed the lack of success in developing a commercial blueberry. Elizabeth persuaded her father to offer test fields at Whitesbog, and she would assist with research. Coville accepted the invitation, and thus began a partnership that culminated in the commercial blueberry. Blueberries are a compliment the cranberry business – they prefer the upland areas of the pine barrens that are too dry for cranberries, and the blueberry harvest occurs in the summer before cranberries are ready. Elizabeth paid local “pineys” to help with the project. She printed flyers and gave each picker a kit: an aluminum gauge for sizing wild berries; jars with formalin to preserve the fruit, and wooden plant labels to mark the bushes.

She paid $1 to $3 for marking any bush with large berries, and paid again to guide her to the bushes, which she then dug up and moved to test plots at Whitesbog. Cuttings from the most promising plants were sent to Coville in Washington, D.C., who hybridized them in government greenhouses. When the resulting seedlings were a year old, they were sent back to Elizabeth’s trial fields at Whitesbog. The first commercial crop was harvested at Whitesbog in 1916. The plants that resulted from this partnership went on to establish commercial blueberry farms throughout the world. New Jersey’s state fruit is the blueberry, and it is still one of the top producers of blueberries in the country.

But Elizabeth was so much more than just blueberries, and one of the best parts about walking around Whitesbog is exploring the remnants of Elizabeth’s gardens. Unlike contemporaries who found the pine barrens ugly and desolate (hence the name “barrens”), Elizabeth appreciated the environment not only for its commercial opportunities, but also for the beauty of its native plants. She got permission from the company to live on the property (JJ had only female children, so he left the property and business to a son-in-law). In 1923, Elizabeth built and moved into Suningive, with windows looking out over the first cranberry bog built by her grandfather 70 years earlier and a test field of her blueberry bushes.

She then proceeded to fill the surrounding landscape with native plants that she dug up on her walks. Altogether, there were over 200 different species, including: white cedars, rhododendrons, azaleas, hollies, sweet spire, ferns and pitcher plants. Today, you can wander around the garden and view many of these plants, plus see some of the original blueberry bushes still growing in the test garden (many named for the “pineys” that originally found them in the wild and brought them to Elizabeth’s attention). JJ’s cranberry bogs are still in production, and, although the property is now owned by the state, the bogs are leased to the fifth generation of the family.

Elizabeth’s contributions continued until her death in 1954, at age 83. She was the first woman member and president of the American Cranberry Growers Association and the first woman to receive a citation from the New Jersey Department of Agriculture. She was also concerned with the welfare of migrant workers (Whitesbog employed hundreds each season, many coming from South Philly). She helped establish a school/nursery for migrant children at Whitesbog and encouraged other bog owners to do the same. She also served on President Herbert Hoover’s Migrant Farm Workers Housing Committee and helped establish a facility to train and care for mentally challenged young men.

Elizabeth also enjoyed photography and processed her own negatives. The trust has many of these negatives and photographs in its archives.

Exploring Whitesbog today takes you past not only Elizabeth’s house and gardens and blueberry/cranberry fields, but also the remains of the company town, including: general store (today selling blueberry jams, books, etc.), worker’s cottages and barrel factory, etc..

There’s even an original Sear’s catalog home and giant Franklinia tree (across the road), brought to Whitesbog by Elizabeth, who experimented with their propagation for her native plant nursery. Note: All Franklinia (now extinct in the wild) are descended from specimens brought back from Georgia by Philadelphia’s Bartram family (Botany in Early Philadelphia (pt. 1): Bartram’s Garden – Alligators, American Plants and a Riverside Trail).

Many contain interpretive material about the company town and the cranberry/blueberry business, so are interesting to check out when open. The buildings are leased by a trust and are only open on weekends for special events (check the Facebook page). The park itself is open year round to walkers/drivers from dusk to dawn.

They offer a moonlight hike around the bogs on the Saturday closest to the full moon.

The flooded cranberry bogs at Whitesbog are also a winter stopover for flocks of Tundra swans, making this a fun winter walk (January-ish).

I remember you posting about that blueberry sundae before, but it never fails to make my mouth water. I want to go there so bad! I love blueberry flavoured anything. Also interesting to learn about Elizabeth White.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s my favorite part of summer! Maybe the worst part of covid last year was that they were closed during blueberry season.

LikeLiked by 1 person